Nouabale-Ndoki’s elephant listeners

Phael Malonga and Frelcia Bambi spend up to a five-weeks at a time out in the wilderness of the Nouabale-Ndoki National Park in the Republic of Congo. They are working on an exciting new project capturing sound data across the forest. At the end of 2016, Cornell University’s Elephant Listening Project and WCS-Congo launched a study using hidden microphones to better monitor forest elephant populations and movements, pinpoint the gunshots of poachers, and record the biodiversity in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, Congo.

Both graduates of the Marien Ngouabe University in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, the two bright young scientists took part in the Ndoki-Likouala Large Mammal Survey after completing their studies. The survey covered 36,000 km2 of forest and swamps, and required 12 months of field missions. Following the completion of this mega-task they are both pretty used to spending long periods of time out in the field. Phael and Frelcia started training with the Elephant Listening Project at the end of 2016 and are now fully immersed in making this project work. Here they tell us a bit more about the project and their personal experiences working in the Nouabale-Ndoki National Park.

ZL: Tell me a bit about your missions in the forest – how many days are you generally out in the field for?

Phael and Frelcia: Each rotation we cover three zones during two missions – a mission of 21 days in the park, covering the zone west of the Goualougo River, and then a long mission of 33 days in the eastern sector of the park, and its southern periphery. During the first missions to these zones our goal was to deploy the acoustic units. Our very first mission to the Goualougo area was in October 2017 and then in November 2017 we covered the eastern sector of the park. We returned to the Goualougo area in January this year – repeating the same itinerary but this time to collect and replace SD cards and replace the batteries in the acoustic units. There are eight people in the team, the two of us plus six forest guides.

ZL: What is an acoustic unit? What can they hear? How far away could a gunshot be detected by one of the units?

Phael and Frelcia: The acoustic units are housed in a hard plastic case – inside the case there is the recording unit (about the size of a computer hard drive), plus a microphone and two 6 volt batteries to power the unit. The acoustic units can record noises at a very low frequency that the human ear cannot detect.

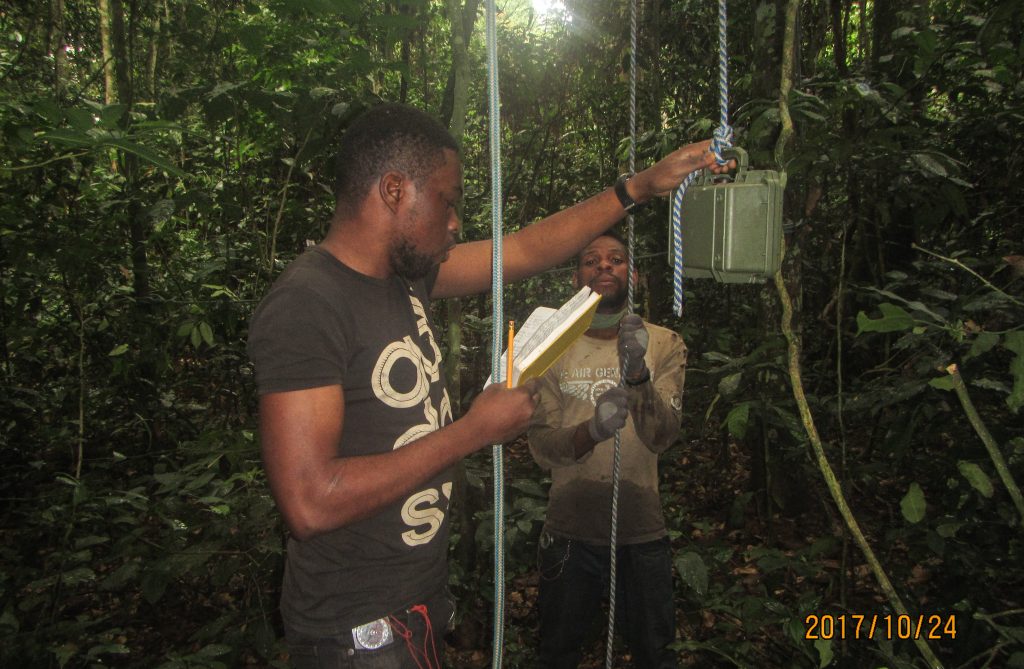

The unit is installed in a tree at a height of between 7 and 15 metres. We have climbing equipment with us and have both been trained in tree rope access to install the units. Once the unit is installed it records anything that emits sound, but what we are mostly interested in are elephant vocalizations and gunshots. For elephants – we can detect vocalisations up to 1 km, while gunshots can be detected up to about 2 kilometres away from the unit.

ZL: What do you do on a general day on one of your missions in the forest?

Phael and Frelcia: When we are out on a forest mission – we are there to collect information. We get up early – at 5am – and we start working between 6.30 and 7. We need to get from one unit to another – a distance of 5 km on average, usually through thick forest with no direct trails. This generally takes half a day of walking depending on the terrain and forest type. Once we get to the installation site we install the unit and at the end of the day we need to find a place to make camp for the night, where we can put up our tents or hammocks, cook our food, and eat. The next day we complete the same routine.

This type of walking is different to walking in a town… we need to be very attentive and alert to make sure that we don’t bump into potentially dangerous wild animals. While we are walking we also collect data on the presence of elephants, wildlife signs, and signs of humans using a Cyber Tracker device. We also use a GPS and compass to navigate. We rotate between who is responsible for navigating and who is responsible for data collection each day.

ZL: Do you have any advice for other young Congolese scientists/conservations on what it takes to be able to do this work?

Phael: I finished Marion Ngouabe like all my colleagues and I know that all of us leaving university are very motivated but it is difficult to find work opportunities. Many people only want to work in the city and not in the forest. My advice for students who have just graduated is to get some field experience, since what we learn at university is mostly theoretical.

To come work here you need to like the forest, you must be motivated to work because working in the field is challenging. You have to be brave to do this job – you have to climb high up into trees in the remote forest. You need to be focused to ensure your and your partner’s safety.

Felcia: To my colleagues who are looking for work or who have finished their studies, I must warn them that working in the forest isn’t easy but every job is difficult at the beginning. You need to have courage to stick it out. But mostly you need to enjoy what you are doing with your life. If today a student arrived to work in the park like us, it will be difficult in the beginning, but if you like the work, and if you are motivated to work like we do – you just need some courage and time to get used to it. You also need to be motivated and hard working. We are here to welcome you like we were welcomed into the project.

ZL: What is the most incredible thing that you have seen during your time in the forest?

Frelcia: The most exciting thing I have experienced in the forest is to be face to face, at a few metres, from a big elephant in its natural habitat. For me, up until now, that is the most remarkable thing I have experienced during my time in the forest.

Phael: I agree with Frelcia, coming face to face with an elephant is very exciting. I saw many during the Ndoki-Likouala Large Mammal Survey, but while working on this project I saw the biggest elephant that I have ever seen. I couldn’t believe that an elephant could be so gigantic! I will never forget that day.

The team preparing and installing an acoustic unit deep in the Ndoki forest.

Any animal (including humans) that makes a loud noise can be detected and recorded by the acoustic devices that the team sets out and monitors in the field. Elephants are exceptionally good subjects for acoustic monitoring because they communicate using low frequency rumbles which can travel long distances across the forest and can be easily picked up by the microphones. By counting vocalizations across a grid of microphones, the project aims to estimate the number of elephants and follow their movements in response to food availability, hunting pressures, and logging activity.

To help speed the analysis of the recordings, ELP has developed sound analysis tools which can automatically identify elephant vocalizations, saving thousands of hours of manually reviewing the sound spectrograms. Using similar automatic sound analysis tools, we are also testing a prototype real-time gunshot detector that can record gunshots within 10 square kilometers of forest and send the signal to an anti-poaching command center for quick response.