Building a Constituency for Conservation in the Ndoki landscape

Conservation of wildlife requires the active support of local people. Ensuring that families tangibly benefit from the protection of wildlife populations is key to garnering support and building a local constituency for conservation. Finding ways to improve the wellbeing and secure the cultural identity of traditional and Indigenous Peoples is a challenge everywhere. In isolated places like northern Republic of Congo, families have limited access to markets, lack social services like schools and health clinics, and have few opportunities for employment. It is not surprising that some local people hunt and sell wildlife when the price of a kilogram of antelope meat is 20 times that of the plantains they grow in their fields.

One benefit of the Nouabale-Ndoki National Park, which covers four thousand square kilometers of pristine rainforest in northern Republic of Congo, is that it serves as a source area of wildlife that disperse into community hunting areas on the park periphery. They are a good source of wild meat for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, but demand for wildlife as food in provincial towns like Ouesso and Pokola is growing—placing increasing pressure on the wildlife in some community areas. If wildlife is depleted in the forests surrounding the park, traditional families will lose a vital source of nutrition and cultural identity, and hunters might be motivated to enter the Park.

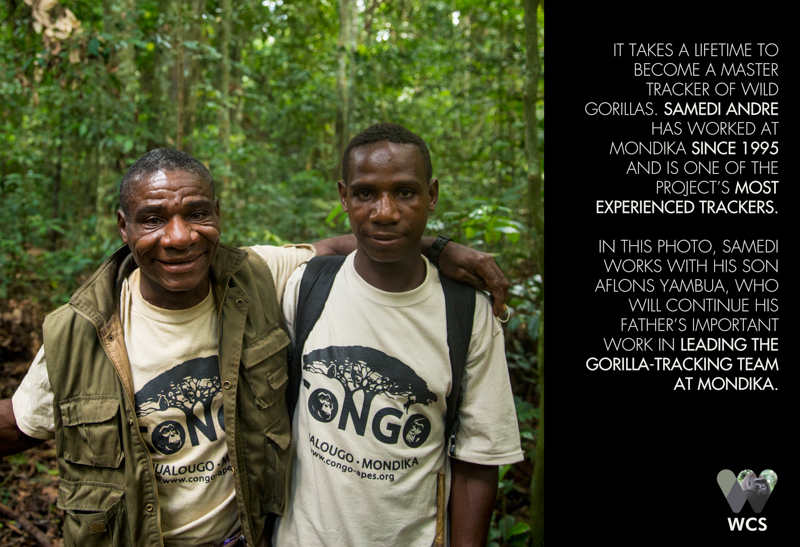

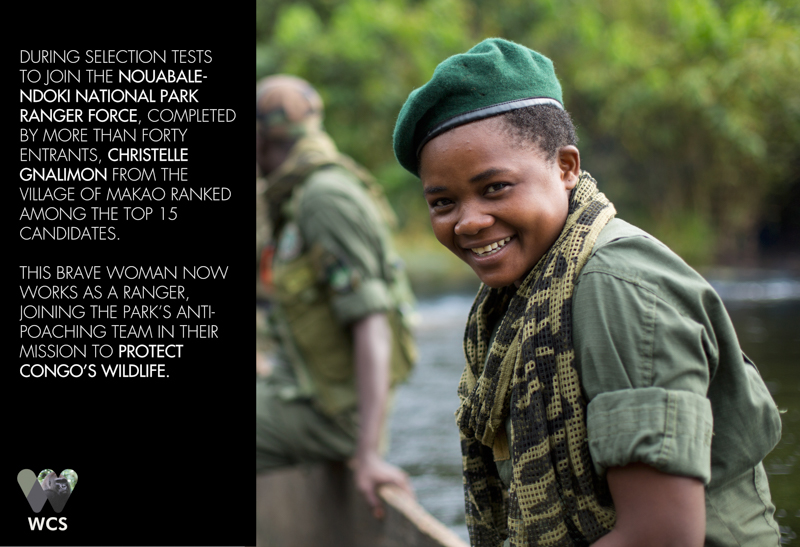

To ensure that hunting remains sustainable in community areas bordering the Park, the Nouabale-Ndoki Foundation is working with over 380 households in Bomassa and Makao, NNNP’s two closest communities. The Nouabale-Ndoki Foundation is focusing on a combination of strengthening community governance and capacity to manage hunting and fishing in their lands and waters, educating the next generation, providing families with access to health services, and offering employment and alternative income generating opportunities to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in the park periphery. These actions are helping to improve the wellbeing of families, secure the hunting and fishing life-ways and cultural identities of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, and building a constituency for the Park and wildlife conservation.

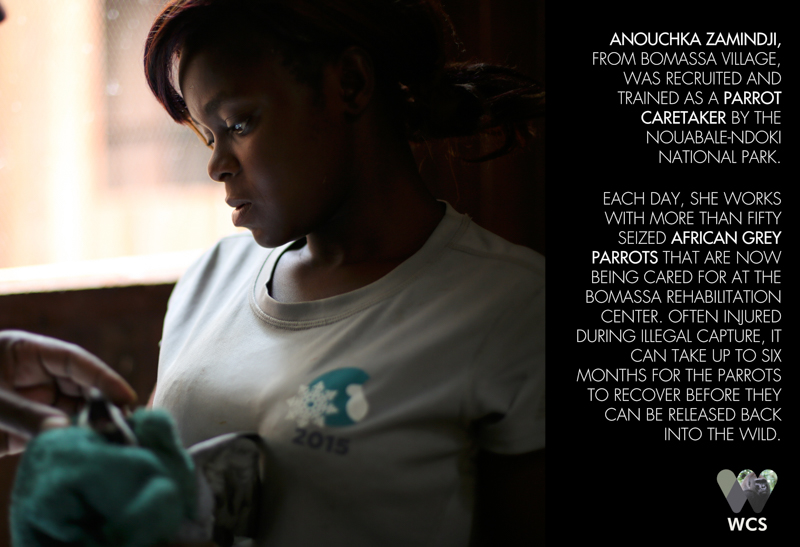

With support from the park, local fishing associations in the park periphery now manage fishing under a fisheries charter to promote sustainable practices and off-take, including using fishing nets with larger mesh and protecting spawning sites. The charter is founded on locally-defined rules for fishing, developed collectively with traditional fishermen and local authorities. It has now been widely adopted within communities living around the park, who have fully supported its implementation within their traditional fishing grounds. Close collaboration with local communities during the implementation of the fisheries charter resulted in a group of fishermen from a nearby village providing information to the park’s law-enforcement team on illegal African Grey Parrot trafficking gangs operating along the Sangha River, intelligence that led to the arrest of the perpetrators and the seizure of nearly 100 captive parrots.

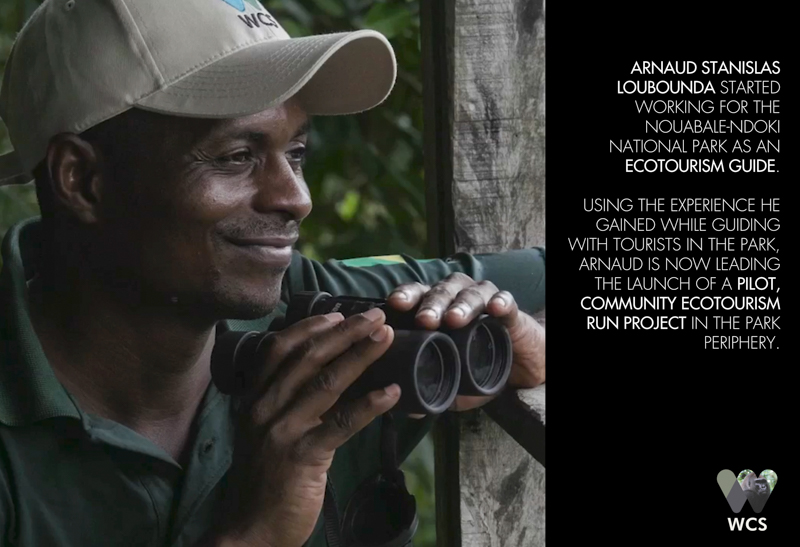

The park also has launched a pilot, community-run ecotourism project to share knowledge on income opportunities through tourism with local communities in preparation for the planned expansion of this industry in the park and its periphery. The park directly employs nearly two hundred people from Makao and Bomassa villages, injecting over 90,000 USD into the local economy each month. Assessments of family wellbeing using the Basic Necessities Survey method has shown that families with members that have jobs associated with the park are better off.

”When I was nine years old, I started participating in “Club Ebobo” (an environmental education initiative launched by the park). We saw gorillas, we saw elephants. The Nouabale-Ndoki National Park has really made a difference for me personally. Thanks to this park, I began to gain an understanding of what it means to protect biodiversity. It is truly marvellous!`` - Elie Gael Gnondo Gobolo, student from Bon-Coin

In rural Congo families still see the government and large private sector businesses like logging and mining companies as the only source of jobs and social services. The Nouabale-Ndoki Foundation is helping to empower local communities to see that they are not simply passive beneficiaries, dependent on the largesse of government and the big companies. By taking more control over the use of their natural resources, and building their own small enterprises they can secure their own futures, creating new opportunities that better address their needs.

The Nouabale-Ndoki National Park lies at the heart of one of the richest and most biologically intact tropical-forest ecosystems in Africa. The park is managed by the Nouabale-Ndoki Foundation, a public private partnership between the Congolese Government and WCS Congo Program. The park’s work with local communities is made possible through funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service and the Sangha Trinational Foundation (FTNS).

Pingback: Nouabale-Ndoki National Park celebrates 25th Anniversary – WCS Congo blog

Pingback: Le parc national Nouabale Ndoki fête son 25ème anniversaire – WCS Congo blog