Stories and history of Mondika

At the edge of Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, in a truly remote part of the northern Congo rainforest, the last 25 years have seen the Mondika research site evolve from a modest forest camp, into one of the world’s most important centres for studies on the western lowland gorilla, thanks to the dedication of a long line of incredible people. This is the history of the site, in their words.

Diane Doran-Sheehy looking through binoculars, 1998 ©Natashah Shah

Diane Doran-Sheehy looking through binoculars, 1998 ©Natashah Shah

It all started with “a roof over a tent that Diane and I shared, and another tent shared by the trackers” remembers Natasha Shah, the very first research assistant of Mondika who came with Professor Diane Doran-Sheehy to establish the camp. “We were looking for a place along water, we hiked in and got unbelievably lucky” explains Pr. Doran-Sheehy of Stony Brook University. Gorillas and chimpanzees were everywhere around them.

At that time, next to nothing was known about western lowland gorillas, “all of our knowledge was coming from mountain gorillas, in the Virunga” admits Pr. Doran-Sheehy, “it was hard to believe that there was one ape we didn’t know anything about. Apes are human’s closest ancestors, we had to understand them”. But western lowland gorillas, who only live in the dense Congo Basin forest, are hard to even approach, “it was the remaining nut to crack. The most difficult species to study. And I felt I had something to bring”.

Mopetu and Pr. Diane Doran-Sheehy studying gorilla dung. Mopetu was one of the first two trackers at Mondika in 1995 and still works there. ©Natashah Shah

Mopetu and Pr. Diane Doran-Sheehy studying gorilla dung. Mopetu was one of the first two trackers at Mondika in 1995 and still works there. ©Natashah Shah

“At the beginning we spent a lot of time learning what gorillas ate by identifying the seeds found in their dung” explains Natashah. Research started from scratch, in an intact part of rainforest where very few scientists had ever come before. “When we first arrived at Mondika, many animals were “naïve” as they had limited or no experience with people. Thus, they often reacted to our presence with curiosity rather than fear” Natashah continues. Stuck between two rivers, the Djeke triangle where Mondika sits was then a two-day trip from Bayanga, in CAR, a very remote area, “that has had minimal to no human disturbance or hunting for probably a century”.

Gathering the right people in the wrong country

To be able to study gorillas up close, and base research on direct observation, they had to “habituate” great apes to human presence. “The point of habituation is to have the animal to ignore you as if you were part of the forest” explains Pr. Doran-Sheehy. Habituation is a hard, stressful process that can take years, and depends on one crucial skill: tracking.

“Lowland gorillas have much bigger ranges than mountain gorillas. Habituation wouldn’t have been possible without expert tracking” tells Pr. Doran-Sheehy. This expertise came from people who know this forest best: Indigenous People. “The Ba’Aka trackers were such wonderful teachers, and taught us so much about the forest – the animals, plants, their stories” adds Natashah Shah.

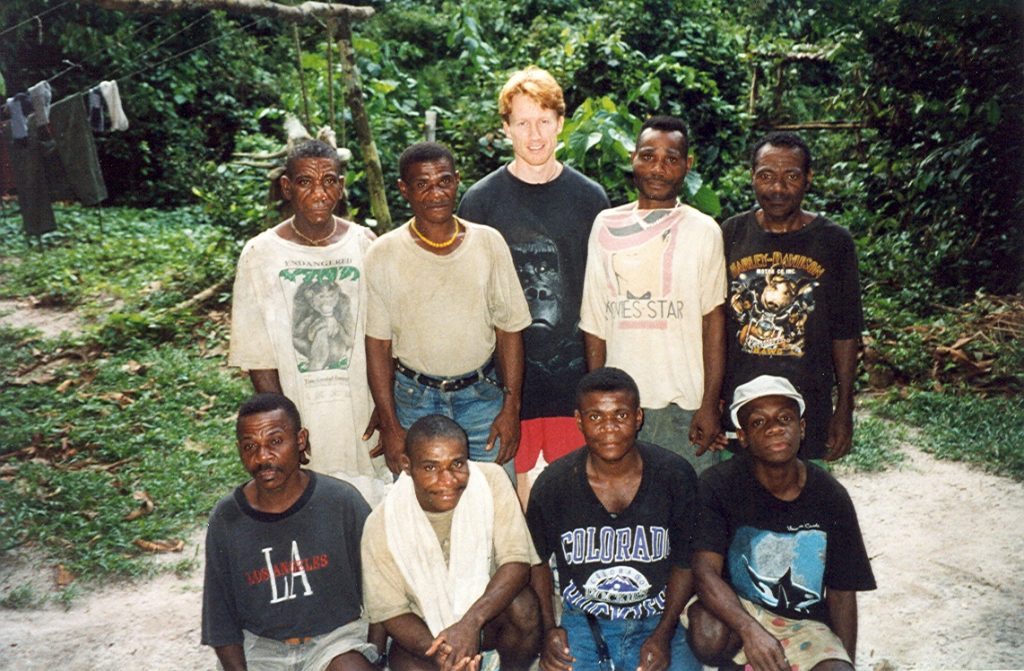

David Greer (middle up) with Mondika trackers (from left top to bottom right): Ndoki, Mesane, Mopetu, Mokonjo, Mongambe, Samedi, Mamandele, and Mangombe) around 1998-2000 ©David Greer

David Greer (middle up) with Mondika trackers (from left top to bottom right): Ndoki, Mesane, Mopetu, Mokonjo, Mongambe, Samedi, Mamandele, and Mangombe) around 1998-2000 ©David Greer

While working on habituating a first group of gorillas, Ba’Aka trackers in Mondika started mentoring their own children to pass on their knowledge, and got nicknamed “the professors” by everyone who has come to work with them. “Since Mondika, I have worked in many places where we track gorillas, but those guys in Mondika were always the cream of the crop” acknowledges David Greer, who arrived in Mondika In 1998 as a researcher, and stayed as the site manager, “they are the best trackers I have ever met.”

“What made Mondika special is that it was a project that had westerners, Ba’Aka, and Bantu together” emphasizes Pr. Doran-Sheehy, “Layers of societies from the US, CAR, Congo, would live together. We ate together, and every Saturday night, we put on music and danced all together.” This atmosphere played a big role in the success of research work in Mondika. Living conditions were rough and habituation was difficult, but teamwork took over.

A Saturday night in Mondika, 2002 ©Tim Rayden

A Saturday night in Mondika, 2002 ©Tim Rayden

It took more than 5 years to realize that Mondika was actually in Congo, and not in CAR. “At that time GPS units were still not accurate”, recognises Natashah. Management of the site changed, yet despite this change, and to this day, the team of trackers remains the same, coming from Bayanga, in CAR. Some of the original professors have given way to their students, passing on the same unique expertise.

“It was challenging but beautiful”

“The density of gorillas in Mondika is really really high, and for habituation it’s not a key ingredient, because you could get confused following tracks. You start following a group, and end up following another one” explains David Greer, who worked to habituate Kingo’s group, the first one to be habituated in Mondika.

“During his habituation, Kingo had a lot of encounters with other males who heard him being afraid of us.” Regrets Pr. Doran-Sheehy. Yet habituation is a necessary evil. It allows the animals to be studied and better understood, “the later point is that you protect them. Kingo is alive. That’s unheard of.”

Kingo, in the swamps of the Mondika river, 2002 ©Tim Rayden

It has now been about 20 years since this 42 year-old silverback has been habituated, and this longevity is indeed remarkable. It took a lot of effort, following his group for months at a time, but it was worth it. “I have worked with 40 to 50 silverbacks in my life, and Kingo was one of the nicest I have ever known. While I was there, he never attacked us, forgiving us when we got too close or when we forgot to vocalize. He is such a good group leader, and a good defender of his group” recognises David Greer, who has kept on working with gorillas since then.

The key to success for the habituation of Kingo’s group was to change the protocol: “The teams needed to go to the swamps to follow the gorillas, where we could see and be seen constantly. The gorillas couldn’t run away, and that sped up the process” explains David Greer. Thanks to that idea, the team could follow the group for 3 consecutive months, when it could only follow it for 10 days previously.

Since then, another group, Buka’s, got habituated in around 2006, and a third one more recently, Metetele’s, starting mid-2019. Those habituated groups have allowed field teams to gather precious data. Pr. Doran-Sheehy remembers that at the time she created Mondika, “the idea that gorilla eat fruits was crazy. Something that basic wasn’t known”.

Nowadays “we know that they have an ecological map in their head, they know exactly where to go, at what season, to find fruits. We know what kind of plants they eat when they are sick”, explains Patrice Mongo, who succeeded David Greer as the site manager in 2003. Patrice was the first Congolese site manager in Mondika, and the longest-lasting. This experience made him grow a passion for apes he never let go.

“Mondika is now a site where gorillas have been studied over the long term, which allows us to answer many research questions that rely on data collected over years or decades” adds Natashah Shah.

Kingo, in 2018 ©Kyle de Nobrega

“Gorillas are a force for good”

“In Rwanda, during the war [1990-1994], neither side wanted to hurt the gorillas, because they knew gorillas were a great tourism opportunity. Gorillas are a force for good” explains Pr. Doran-Sheehy. And she had a vision for Mondika: “I wanted tourism and research to go hand in hand, both would enhance each other. Tourism can be a very important component of a conservation project, but it has to be controlled, especially to protect the animal’s health. It has to not become a zoo. It’s a place to see the animal behave naturally.”

Sadly Pr. Doran-Sheehy ended up running out of funds. “It’s one of those ironies”, she remembers: “once we ensured that this area wouldn’t be logged, we started losing funds”. That’s when management of the site was handed over to WCS Congo. “I was very grateful to hand it over. I was afraid to leave the animal unprotected.” And that’s when tourism became a source of income for the site, as well as an excellent deterrent to poaching.

“Any site which does tourism has a responsibility to do research alongside it. You have to collect data from sunrise to sunset. Research is a critical component, and applied research must guide the tourism program” adds David Greer. Since 2016, a fruitful continuing partnership between the Goualougo Triangle Ape Project and the WCS started, and succeeded to secure funds for research as well as tourism.

In 2014, management of Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park strengthened thanks to the creation of a Public-Private Partnership between WCS and the Republic of Congo. This impacted Mondika, by reinforcing anti-poaching efforts around the Park too.

Since 2020, WCS took steps towards making Pr. Doran-Sheehy’s vision a reality. A new partnership with the Congo Conservation Company (CCC) aims to develop responsible tourism in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park. In support of this new partnership, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is providing generous support to create the enabling conditions needed to ensure the development of sustainable tourism operations, that ensure the safety of the animals, by respecting IUCN best practice, and that promote the well-being of the Park’s local communities and Indigenous Peoples.

A tourist in Mondika, 2018 ©Kyle de Nobrega

A tourist in Mondika, 2018 ©Kyle de Nobrega

In addition, to ensure the safety of the gorillas in perpetuity, the Djeke triangle, which includes Mondika, will hopefully soon become part of the Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park. To do so, the WCS can count on the support of Rainforest Trust, and will work closely with communities and scientists, will engage with government and logging companies to make sure it becomes a stronghold for the incredible wildlife it harbors.

This would be a firm step to safeguard the hard work of all the men and women who spend months, years, and decades in the forest, tracking, observing and studying its wildlife. “The annexation of the Djeke triangle into the Park is long overdue” reminds David Greer: “it is such a special place, an amazing pristine area, with an unbelievable amount of biodiversity, and an incredible density of chimpanzees and gorillas”.

A special place in the heart of the rainforest

“It was a magical experience to be in the midst of all of these animals and observe them close-up without disturbing them” testifies Natashah Shah. “I remember, in 1995, the animals did not try to run away from us but seemed just as curious and eager to get a look at us as we were about them! Those are some of my most cherished Mondika memories.”

“The most striking moment I lived in Mondika was when I saw one of Kingo’s female give birth” remembers Patrice Mongo. “It was a little miracle: she was pregnant, we were following them, and it feels like it only took a minute, she just went around a tree, and when she reappeared, she had a baby in her left hand, still attached by its umbilical cord. You need months and months of observation to be able to see this kind of scenes”.

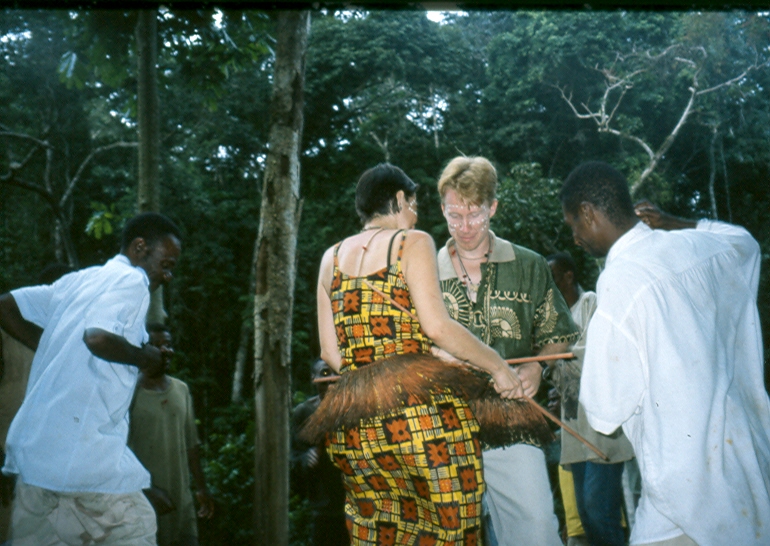

“I met my wife in Central African Republic, she was working at Bai Hokou, in Dzanga Sangha, habituating gorillas for WWF” tells David Greer. “We got married in 2001, in the forest, according to the Ba’Aka tradition. The only formal part was exchanging sticks. Then I remember lots of food, drinks, music and dancing. We felt married, bonded through our passion of the forest and our work.”

Chloé Cipolletta et David Greer, entourés des pisteurs Mondika, Mokondjo et Ndima, célébrant leur mariage selon la tradition BaAka ©David Greer.

Chloé Cipolletta et David Greer, entourés des pisteurs Mondika, Mokondjo et Ndima, célébrant leur mariage selon la tradition BaAka ©David Greer.

Pingback: Important Piece in the Congo Conservation Puzzle in Place! | Cincinnati Zoo Blog

Pingback: Conservation: Le parc national de Nouabalé-Ndoki célèbre ses 30 ans – Mayilanews